In the previous post we looked at the history of Road Tax, the previous (pre-April 2017) VED scheme and the effect of graduated VED on the UK car market.

We are now going to look at the VED Reform scheme itself, how it is implemented and some of its impacts.

VED Reform scheme

VED Reform made changes to both the 1st year VED rates (when a car is first registered) and to the standard VED rates (that are due each time the previous VED expires - usually annually).

The change to the 1st year rate is, in my opinion, the right idea, but poorly implemented. As we saw in the previous post, there was a big step change in VED rate from those vehicles with CO2 emissions of 130g/km or less and those above 130g/km - £130 in fact. All vehicles with CO2 emissions of 130g/km or less paid £0 (zero) VED in their first year. As we saw in this chart, at the end of 2016 75% of cars registered paid no VED in their first year.

This big step change in VED was a significant incentive for vehicle manufacturers to try and get their vehicles to 130g/km or less. If they could get their vehicles to 100g/km or less then those vehicles would never pay any VED.

The trouble with this was that once you'd reached 100g/km (and to a lesser extent 130g/km) the incentive to keep improving CO2 emissions was diminished (unless the vehicle featured heavily in the Company Car market where each 5g/km improvement was still incentivised). Also, 0g/km to 100g/km was a very wide band, which didn't sufficiently incentivise ZEV (Zero Emission Vehicles) or ULEV (Ultra Low Emission Vehicles), i.e. electric vehicles or plug-in hybrid, whose CO2 emissions were typically at 50g/km or below.

What the 1st year VED needed was a more progressive rise in duty as CO2 emissions increased. Fortunately, this is what we got (sort of). The table below shows the pre and post-April 2017 1st Year VED rates. [Note the renaming of the CO2 bands. However, since VED Reform was introduced DVLA seem to have depreciated the use of names for the CO2 bands]

It's far from perfect: there is still a big step change in rate at 76g/km, but at least ULEV and ZEV are incentivised more strongly and every vehicle that emits CO2 pays VED. In addition, the vehicles with the highest CO2 emissions have their VED rates increased to further discourage their use. [Note that some low emitting vehicles, i.e. those between 76 and 130g/km see a significant rise in 1st Year VED]

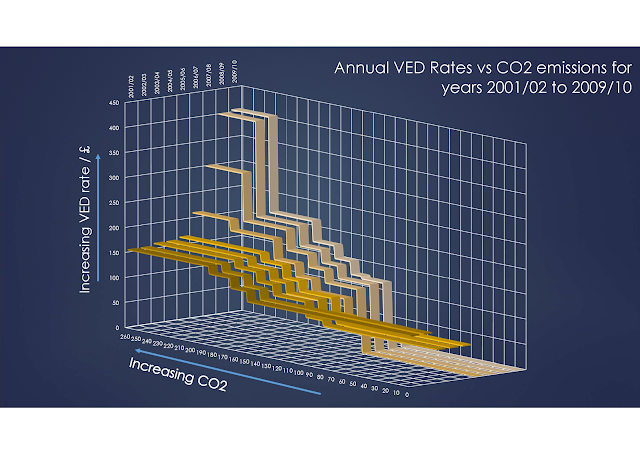

If we look at our now familiar ribbon chart we can see how the VED rates have changed with the introduction of VED Reform.

The new rates are shown in red and the larger steps in the higher rates can easily be seen. The rate bands between 1-50g/km (£10) and 51-75g/km (£25) are much harder to pick out.

So far, so good(ish). However, the standard VED rates also need revising.

The revisions to the 1st year VED rates are good and welcome - up to a point. They are a "one-off" duty charge that actually has little effect on the ongoing cost of ownership. An extra £20, £50, even £100 on the price of the average city runaround is not going to make a great deal of financial impact on the consumer compared with the purchase price of the vehicle. For example, in 2016, the average list price of an "A Segment" City Car was approx £9,900, the average increase in VED rate for the 1st year would be approx £160 or about 1.6% of the previous purchase price (this estimate will be covered later). The more expensive the car, the less difference the increase in VED will make.

The annual VED rate is much more important to the consumer or owner of the vehicle as this has to be paid each year and it is one of the key metrics (along with fuel, servicing and and insurance costs) consumers look for when choosing either a new or used vehicle. The VED rate is one of the contributing factors to the Cost of Ownership, i.e. how much you have to spend to keep the car on the road. So a vehicle with a low annual VED rate is going to be more desirable than a similar vehicle with a higher VED rate as you'll have to spend less money on VED to keep it on the road.

As we saw previously (see table above), under the old VED scheme, the standard (annual) VED rate also increased in line with CO2 emission, but not to the same extent as the 1st year rate. Under VED reform, for vehicles that emit even 1g/km CO2 the new standard (annual) rate would be a flat £140. It would NOT take into account the CO2 emissions of the vehicle.

Take a look at the right hand column of that table. For each VED band it shows the change in standard VED rate from the old VED scheme to the new one. Note how the lowest emitting vehicles now pay much more VED each year than they did previously and the highest emitting vehicles pay much less VED each year.

So what does that look like on our familiar ribbon chart?

Note the "flat line" for the new annual scheme: as far as the annual VED rate is concerned, there is NO incentive to choose a car with low CO2 emissions as all cars with CO2 emissions of 1g/km or more will pay the same £140 per year rate. This would apply particularly to used cars where someone else has already paid the First Year VED.

However, it doesn't stop there, if the vehicle price was over £40,000 when it was first registered, the annual (renewal) VED rate would be increased by £310 per year for 5 years (this is usually years 2 to 6 of the vehicle's life), after which it reverts to £140 (or whatever the prevailing standard rate is at the time). Let's just think about what this means: the amount of VED due on a vehicle in future years is linked to the vehicle's price (when new). Price is a metric that is NOT collected as part of the process of registering a vehicle by any of the parties involved (manufacturer, retailer, DVLA or SMMT). This is a very significant change to the registration system in the UK and as we will see later one that would cause a great deal of upheaval in the industry.

Before we do that, let's have a look at the complete new VED Reform scheme:

Vehicle Price

So what is actually meant by "vehicle price"? Well for the purposes of VED Reform, vehicle price was defined as the published value of the vehicle including any factory fitted options, the cost of delivery to dealer premises (if charged), pre-delivery inspection (PDI) and VAT on those items. It would exclude the value of accessories fitted at the dealer and it would exclude the cost of the 1st Year VED and the £55 First Registration Fee (FRF). This is very similar to the P11d value of the vehicle that is used when calculating Company Car Tax.

Different manufacturers have different ways of charging for their vehicles, some include delivery and PDI in the cost of the vehicle, others call them out separately. As a result, there are many different definitions of "List Price" depending on which manufacturer you talk to. At JLR, to try and avoid confusion, we chose to call the DVLA's definition of a vehicle's price the "DVLA List Price" to differentiate it from any other meaning of "List Price". For clarity, I will continue to use "DVLA List Price" for that same reason.

Note that on the slide above, there is no mention of discounts or trade-in values for part exchanges in the calculation of DVLA List Price. The DVLA List Price is NOT the price the customer pays for the vehicle. Customers who pay less than £40k for their vehicle (because of discounts or trade-ins), may nevertheless find that the additional £310 VED rate was due on their vehicle because its DVLA List Price was over £40k. Similarly, for the increasing number of people who purchase or lease their vehicle based on a monthly payment, the actual purchase price of the vehicle may be irrelevant to them.

When using pricing to calculate taxes and duties, HM Treasury uses the published value of the vehicle the day before it was registered for the first time (or the registration submitted). Not when the customer ordered the vehicle, not when the manufacturer built the vehicle or when it invoiced the retailer. This "definition" of vehicle price is what causes the issues, but why?

Potential impact on the customer

Inevitably, there will be a delay between the time at which a customer places an order for a vehicle, to when it is invoiced to the dealer (by the manufacturer), to when the retailer invoices the customer, to when the vehicle is first registered. That time could be anything from a couple of days to several months (if there is a long waiting list for the vehicle). If any of the values used to calculate the DVLA List Price (published list price, option prices, VAT rate) change during that intervening period, the DVLA List Price of the vehicle will change. This could mean that the vehicle the customer had carefully ordered to come in at £39,995 (to avoid the £310 addition VED rate) now has a DVLA List Price of over £40,000. Meaning the additional VED rate becomes applicable and the customer pays more than they budgeted for. Even if the customer doesn't own the vehicle, for example, if it is leased, then the leasing company will pass the higher VED costs on to the customer in the form of higher monthly payments.

By way of an example, consider the following hypothetical vehicle order:

Note that the VAT rate change on the 1st April causes the DVLA List Price to increase to over £40k and the customer's vehicle become liable for the additional £310 per year VED rate, even though they did their homework and ordered a vehicle with a DVLA List Price below £40k.

Any one of those values that make up the DVLA List Price of the customer's vehicle could have changed between the point at which the customer ordered the vehicle and it being registered. In this case it was the VAT rate, something that neither the manufacturer, retailer or customer have ANY control over.

So what is the potential impact on the customer in terms of additional VED if the DVLA List Price of the vehicle goes over £40k?

A customer could pay up to £1,550 more VED on a vehicle that falls just above the £40k threshold compared with a similar, or even identical, one that falls just below the £40k threshold.

Impact on the manufacturer or importer

Under VED Reform it is the responsibility of the manufacturer or importer to provide the DVLA List Price of the vehicle to DLVA at the point of registration. What this actually means is that when a retailer clicks the button to register a vehicle, the manufacturer or importer must calculate the DVLA List Price of the vehicle in real-time and send it to DVLA along with the other technical details of the vehicle, e.g. CO2 emissions, EU emission standard, colour, etc. That doesn't sound too hard, the manufacturer can just look up into their financial system to see how much they invoiced the retailer for the vehicle and send that figure to DVLA - wrong.

Remember, the DVLA List Price is calculated as the published value of the vehicle the day before the vehicle was registered. Sending the invoice value won't work. The published price of the vehicle, its options or the VAT rate may have changed in the period of time between invoice and registration.

What the manufacturer must do instead is to look back into their systems at what vehicle was built, which options it was fitted with and then calculate what the published value of that vehicle, with those options was yesterday, then add yesterday's VAT rate, and send that value to DVLA. This must all be done within a fraction of a second to ensure it doesn't hold up the registration procedure.

Needless to say that this process of calculating yesterday's DVLA List Price caused a major headache for all manufacturers and importers.

So that's the calculation of the DVLA List Price and the potential issues of that dealt with.

There is another, perhaps unintended, impact of VED Reform that needs to be addressed. This impacts retailers and short term owners of vehicles, for example rental companies.

First Licence Rate (FLR) Refunds

This goes back to the change in the Tax Disc rules in 2014 and is not brought about by VED Reform, however, it is exacerbated by it.

Since the "Tax Disc" was abolished in 2014, when a vehicle is sold, the "tax" no longer transfers to the new owner, it is refunded to the existing/previous owner. However, the full amount remaining is not refunded: only whole months remaining and the pro-rata'd amount is based on the lower of the amount paid or the standard (annual) VED rate.

What the final slide in this sequence shows is that a) because the VED rates for the 1st year have increased significantly, and b) that for some vehicles the annual (renewal) VED rates have decreased, the FLR refund amount is significantly lower than the amount originally paid. In other words, a larger proportion of the FLR is "lost" (to DVLA) when a vehicle changes hands within the first year. This could be as high as £1,860.

This has cost implications for retailers running demonstrator or courtesy vehicles which may be changed three or four times per year. As an example, for a sub-£40k demonstrator vehicle with CO2 emissions of 155g/km that is changed 4 times per year the retailer would lose £1,440 (£360 x 4) per year in "lost" FLR VED each year.

The same would apply to companies running short-term rental fleets. These costs all add up and ultimately will have to be passed on to the consumer, either as higher prices, or reduced availability of rental, demonstrator or courtesy vehicles.

Next time, we'll look at how VED Reform has impacted the UK car market since it was introduced.

VED Reform scheme

VED Reform made changes to both the 1st year VED rates (when a car is first registered) and to the standard VED rates (that are due each time the previous VED expires - usually annually).

The change to the 1st year rate is, in my opinion, the right idea, but poorly implemented. As we saw in the previous post, there was a big step change in VED rate from those vehicles with CO2 emissions of 130g/km or less and those above 130g/km - £130 in fact. All vehicles with CO2 emissions of 130g/km or less paid £0 (zero) VED in their first year. As we saw in this chart, at the end of 2016 75% of cars registered paid no VED in their first year.

This big step change in VED was a significant incentive for vehicle manufacturers to try and get their vehicles to 130g/km or less. If they could get their vehicles to 100g/km or less then those vehicles would never pay any VED.

The trouble with this was that once you'd reached 100g/km (and to a lesser extent 130g/km) the incentive to keep improving CO2 emissions was diminished (unless the vehicle featured heavily in the Company Car market where each 5g/km improvement was still incentivised). Also, 0g/km to 100g/km was a very wide band, which didn't sufficiently incentivise ZEV (Zero Emission Vehicles) or ULEV (Ultra Low Emission Vehicles), i.e. electric vehicles or plug-in hybrid, whose CO2 emissions were typically at 50g/km or below.

What the 1st year VED needed was a more progressive rise in duty as CO2 emissions increased. Fortunately, this is what we got (sort of). The table below shows the pre and post-April 2017 1st Year VED rates. [Note the renaming of the CO2 bands. However, since VED Reform was introduced DVLA seem to have depreciated the use of names for the CO2 bands]

It's far from perfect: there is still a big step change in rate at 76g/km, but at least ULEV and ZEV are incentivised more strongly and every vehicle that emits CO2 pays VED. In addition, the vehicles with the highest CO2 emissions have their VED rates increased to further discourage their use. [Note that some low emitting vehicles, i.e. those between 76 and 130g/km see a significant rise in 1st Year VED]

If we look at our now familiar ribbon chart we can see how the VED rates have changed with the introduction of VED Reform.

The new rates are shown in red and the larger steps in the higher rates can easily be seen. The rate bands between 1-50g/km (£10) and 51-75g/km (£25) are much harder to pick out.

So far, so good(ish). However, the standard VED rates also need revising.

The revisions to the 1st year VED rates are good and welcome - up to a point. They are a "one-off" duty charge that actually has little effect on the ongoing cost of ownership. An extra £20, £50, even £100 on the price of the average city runaround is not going to make a great deal of financial impact on the consumer compared with the purchase price of the vehicle. For example, in 2016, the average list price of an "A Segment" City Car was approx £9,900, the average increase in VED rate for the 1st year would be approx £160 or about 1.6% of the previous purchase price (this estimate will be covered later). The more expensive the car, the less difference the increase in VED will make.

The annual VED rate is much more important to the consumer or owner of the vehicle as this has to be paid each year and it is one of the key metrics (along with fuel, servicing and and insurance costs) consumers look for when choosing either a new or used vehicle. The VED rate is one of the contributing factors to the Cost of Ownership, i.e. how much you have to spend to keep the car on the road. So a vehicle with a low annual VED rate is going to be more desirable than a similar vehicle with a higher VED rate as you'll have to spend less money on VED to keep it on the road.

As we saw previously (see table above), under the old VED scheme, the standard (annual) VED rate also increased in line with CO2 emission, but not to the same extent as the 1st year rate. Under VED reform, for vehicles that emit even 1g/km CO2 the new standard (annual) rate would be a flat £140. It would NOT take into account the CO2 emissions of the vehicle.

So what does that look like on our familiar ribbon chart?

Note the "flat line" for the new annual scheme: as far as the annual VED rate is concerned, there is NO incentive to choose a car with low CO2 emissions as all cars with CO2 emissions of 1g/km or more will pay the same £140 per year rate. This would apply particularly to used cars where someone else has already paid the First Year VED.

However, it doesn't stop there, if the vehicle price was over £40,000 when it was first registered, the annual (renewal) VED rate would be increased by £310 per year for 5 years (this is usually years 2 to 6 of the vehicle's life), after which it reverts to £140 (or whatever the prevailing standard rate is at the time). Let's just think about what this means: the amount of VED due on a vehicle in future years is linked to the vehicle's price (when new). Price is a metric that is NOT collected as part of the process of registering a vehicle by any of the parties involved (manufacturer, retailer, DVLA or SMMT). This is a very significant change to the registration system in the UK and as we will see later one that would cause a great deal of upheaval in the industry.

Before we do that, let's have a look at the complete new VED Reform scheme:

The figures in red indicate where a vehicle would pay LESS annual VED under the new VED Reform scheme than they did under the previous scheme. Note that those vehicle have the highest emissions and that those vehicles with the lowest emission all pay MORE VED (with the exception of ZEVs under £40k).

Let's look at some examples of what these new rules mean:

There is quite a wide range of CO2 emissions across those three vehicles, but they all pay the same £140 annual VED rate.

There are a few perverse outcomes of the new rules too. On the slide above, we can see that the BMW i3 and the Tesla Model S both emit 0g/km of CO2 (as they are both pure electric vehicles), but that the Tesla pays £310 per year annual VED rate because it is over £40k.

The Ford Mustang on the other hand, despite it putting out 299g/km CO2 pays only £140 per year annual VED rate because it is under £40k. That's the same as a BMW i3 RX which emits just 12g/km CO2.

If we generalise a little and split the 2016 car market by published price and CO2 emissions we can see how different vehicles are impacted.

The table on the left splits the 2016 car market by CO2 emissions and by published price (above and below £40k). The percentages are the proportion of the market represented by vehicles with those CO2 emissions and published price. The green and red shading reflects those vehicles with the lowest and highest CO2 emissions.

The table on the right shows whether those same 6 generalised vehicles categories win (green minus) or lose (red plus) under the new VED Reform scheme. Whether it was intentional or not can be argued, but what can't be argued is that the lowest CO2 emitting vehicles are all worse off under VED Reform and that the highest emitting vehicles are better off under VED Reform.

So what is actually meant by "vehicle price"? Well for the purposes of VED Reform, vehicle price was defined as the published value of the vehicle including any factory fitted options, the cost of delivery to dealer premises (if charged), pre-delivery inspection (PDI) and VAT on those items. It would exclude the value of accessories fitted at the dealer and it would exclude the cost of the 1st Year VED and the £55 First Registration Fee (FRF). This is very similar to the P11d value of the vehicle that is used when calculating Company Car Tax.

Different manufacturers have different ways of charging for their vehicles, some include delivery and PDI in the cost of the vehicle, others call them out separately. As a result, there are many different definitions of "List Price" depending on which manufacturer you talk to. At JLR, to try and avoid confusion, we chose to call the DVLA's definition of a vehicle's price the "DVLA List Price" to differentiate it from any other meaning of "List Price". For clarity, I will continue to use "DVLA List Price" for that same reason.

Note that on the slide above, there is no mention of discounts or trade-in values for part exchanges in the calculation of DVLA List Price. The DVLA List Price is NOT the price the customer pays for the vehicle. Customers who pay less than £40k for their vehicle (because of discounts or trade-ins), may nevertheless find that the additional £310 VED rate was due on their vehicle because its DVLA List Price was over £40k. Similarly, for the increasing number of people who purchase or lease their vehicle based on a monthly payment, the actual purchase price of the vehicle may be irrelevant to them.

When using pricing to calculate taxes and duties, HM Treasury uses the published value of the vehicle the day before it was registered for the first time (or the registration submitted). Not when the customer ordered the vehicle, not when the manufacturer built the vehicle or when it invoiced the retailer. This "definition" of vehicle price is what causes the issues, but why?

Potential impact on the customer

Inevitably, there will be a delay between the time at which a customer places an order for a vehicle, to when it is invoiced to the dealer (by the manufacturer), to when the retailer invoices the customer, to when the vehicle is first registered. That time could be anything from a couple of days to several months (if there is a long waiting list for the vehicle). If any of the values used to calculate the DVLA List Price (published list price, option prices, VAT rate) change during that intervening period, the DVLA List Price of the vehicle will change. This could mean that the vehicle the customer had carefully ordered to come in at £39,995 (to avoid the £310 addition VED rate) now has a DVLA List Price of over £40,000. Meaning the additional VED rate becomes applicable and the customer pays more than they budgeted for. Even if the customer doesn't own the vehicle, for example, if it is leased, then the leasing company will pass the higher VED costs on to the customer in the form of higher monthly payments.

By way of an example, consider the following hypothetical vehicle order:

Note that the VAT rate change on the 1st April causes the DVLA List Price to increase to over £40k and the customer's vehicle become liable for the additional £310 per year VED rate, even though they did their homework and ordered a vehicle with a DVLA List Price below £40k.

Any one of those values that make up the DVLA List Price of the customer's vehicle could have changed between the point at which the customer ordered the vehicle and it being registered. In this case it was the VAT rate, something that neither the manufacturer, retailer or customer have ANY control over.

So what is the potential impact on the customer in terms of additional VED if the DVLA List Price of the vehicle goes over £40k?

A customer could pay up to £1,550 more VED on a vehicle that falls just above the £40k threshold compared with a similar, or even identical, one that falls just below the £40k threshold.

Impact on the manufacturer or importer

Under VED Reform it is the responsibility of the manufacturer or importer to provide the DVLA List Price of the vehicle to DLVA at the point of registration. What this actually means is that when a retailer clicks the button to register a vehicle, the manufacturer or importer must calculate the DVLA List Price of the vehicle in real-time and send it to DVLA along with the other technical details of the vehicle, e.g. CO2 emissions, EU emission standard, colour, etc. That doesn't sound too hard, the manufacturer can just look up into their financial system to see how much they invoiced the retailer for the vehicle and send that figure to DVLA - wrong.

Remember, the DVLA List Price is calculated as the published value of the vehicle the day before the vehicle was registered. Sending the invoice value won't work. The published price of the vehicle, its options or the VAT rate may have changed in the period of time between invoice and registration.

What the manufacturer must do instead is to look back into their systems at what vehicle was built, which options it was fitted with and then calculate what the published value of that vehicle, with those options was yesterday, then add yesterday's VAT rate, and send that value to DVLA. This must all be done within a fraction of a second to ensure it doesn't hold up the registration procedure.

Needless to say that this process of calculating yesterday's DVLA List Price caused a major headache for all manufacturers and importers.

So that's the calculation of the DVLA List Price and the potential issues of that dealt with.

There is another, perhaps unintended, impact of VED Reform that needs to be addressed. This impacts retailers and short term owners of vehicles, for example rental companies.

First Licence Rate (FLR) Refunds

This goes back to the change in the Tax Disc rules in 2014 and is not brought about by VED Reform, however, it is exacerbated by it.

Since the "Tax Disc" was abolished in 2014, when a vehicle is sold, the "tax" no longer transfers to the new owner, it is refunded to the existing/previous owner. However, the full amount remaining is not refunded: only whole months remaining and the pro-rata'd amount is based on the lower of the amount paid or the standard (annual) VED rate.

What the final slide in this sequence shows is that a) because the VED rates for the 1st year have increased significantly, and b) that for some vehicles the annual (renewal) VED rates have decreased, the FLR refund amount is significantly lower than the amount originally paid. In other words, a larger proportion of the FLR is "lost" (to DVLA) when a vehicle changes hands within the first year. This could be as high as £1,860.

This has cost implications for retailers running demonstrator or courtesy vehicles which may be changed three or four times per year. As an example, for a sub-£40k demonstrator vehicle with CO2 emissions of 155g/km that is changed 4 times per year the retailer would lose £1,440 (£360 x 4) per year in "lost" FLR VED each year.

The same would apply to companies running short-term rental fleets. These costs all add up and ultimately will have to be passed on to the consumer, either as higher prices, or reduced availability of rental, demonstrator or courtesy vehicles.

Next time, we'll look at how VED Reform has impacted the UK car market since it was introduced.